Original Items: One-one-of-a-kind. A fantastic grouping that belonged to Robert James McDade ASN 2005464. During WWII he served in the 99th Division, 395th Infantry Regiment, receiving a battlefield commission from sergeant to 2nd lieutenant during the Battle of the Bulge, and later during the post-war occupation was promoted to 1st lieutenant. Shortly after the 99th became the first complete division across the Remagen Bridge, he received a Bronze Star for demining a road under enemy fire. You can read more about his life in his 2009 obituary at this .

Included in this grouping a some letter he wrote to the daughter of his wartime friend in the early 1990s which explain what his role was in the war, the battles they fought in which include the Battle of the Bulge and the Remagen. Here is one letter written by Bob McDade that explains his service in WWII as part of the legendary 99th Division.

August 29, 1993

Dear Gail:

I was glad to hear from you but was sorry to hear about your father. It was good that he did not linger and have a lot of suffering. The annual exchange of Christmas cards was a good tie between us. It always brought back a lot of memories to me. Thank you for the picture you sent. As I looked at the picture I thought I would share some memories of your father and the years we spent together. Also to tell you something about the 99th Division and what Willard did in the service.

I was inducted into the army on November 20, 1942 at Akron, Ohio. My home was Massillon, Ohio, about 20 miles south of Akron. My army travels then took me to Columbus, Ohio and directly by rail to Camp Van Dorn in Mississippi. That is where I met your father. I assume that he left his home in Georgia about the same time I left Massillon.

Our address was A&P Platoon, Hqs. Co., 1st Battalion, 395th Infantry, 99th Division, Camp Van Dorn, Mississippi. That address will explain a lot of the story I want to relate to you.

The 99th Infantry Division was a new land outfit formed at Camp Van Dorn. The Division emblem patch was blue and white in a checker board design. We were known by that patch as the Checker Board Division. Perhaps you saw that emblem on the left arm of your father's uniforms. A division is made up of about 5,000 people so it is a large outfit composed of many smaller companies all trained to work as a team to support the infantry battalions and field artillery. Our A&P platoon was part of the 395th battalion which consisted of 35 officers and 825 men. A division has 3 battalions and these are the heart of the fighting force and consist of the men you see pictures of on the front lines of any war. The rest of the division are the back up and support groups. Our battalion was broken down into 3 identical sections and we were in the headquarters company of the 1st battalion of the 395th. The headquarters company was split into 5 platoons and the A&P platoon was one of those.

The above is a brief explanation of what a division is and how it is subdivided into smaller units so ea division can be specially trained to do their job. You are now probably wondering what in the world an A&P platoon is and what are their jobs and responsibilities. Willard and I were assigned to this platoon as soon as we arrived at Camp Van Dorn ad we were with that platoon until the division came home after the war. A&P stands for Ammunition and Pioneer. The ammunition part of the name means we were responsible for handling all the ammunition needs of the 1st section of the 395 battalion. Our platoon had 2 ton trucks like you see soldiers riding in and Jeep with trailer. One of the trucks was used to carry ammunition at all times. We were like a moving ammunition store and had to be well stocked and ready to deliver ammunition to the front line companies A-B-C-D immediately when they needed it. We would use the jeep and trailer to make our deliveries to them. Our supply depot was some distance behind the front lines and we had to replenish our supplies from frequent trips to them. In some areas where there was a lot of fighting we would have a supply of our ammunition on the ground in addition to what we had in the truck so our supply would meet the demands of men on the front.

Now that you know all about the 99th division right down to the A&P platoon, let me tell you about the men of the platoon. There were 38 of us from several states but mostly from Ohio, Pennsylvania, North Caroline, Georgia and Alabama. Can you envision 37 of us rookies and 1 lieutenant getting together for the first time with 3 training sergeants. We were all housed on the second floor of a barracks. They were still building parts of the camp when we got there and we were used to build some wooden walks between buildings to keep out of the mud when it rained.

During the first year of training three of us were promoted to sergeants. Each of us was in charge of 11 men and each had a corporal responsible to us. We reported to a staff sergeant and a Lieutenant was in charge of the platoon. Your father and I were two of those 3 sergeants. On January 28, 1945 during combat I received a Battlefield Commission as a Lieutenant and was put in charge of the platoon so I was able to stay with the same men I had always been with previously.

You have probably seen posters or heard about - Join the Service and see the World. The men of the A&P platoon did not see the world but we did get to places we would never have seen if we hadn't been with the 99th Division. We had basic training, maneuvers and nearly a year at Camp Van Dorn, Mississippi before moving on to Camp Maxey, Texas in the fall of 1913 for additional training. August of 1944 was the beginning of getting ready to leave the United States for the war in Europe. It takes a lot of time and planning to get a division of people and equipment ready to move overseas and be combat ready in a short time after arriving in Europe.

In early September we went by train to Camp Miles Standish, a short distance from Boston, Massachusetts. We were there three weeks while they gave us shots and loaded our equipment on Victory Ships. Our division sailed out of Boston harbor in a long company of large ships. That is quite a sight to be on the ocean and see ships as far_as you can see. It took us 13 days to cross the ocean before we landed at Glasgow, Scotland. They immediately put us on a train and we rode south through England to Dorchester which is in south western England not far from the English Channel. We were in an English camp for three weeks while we got our equipment and made ready to move on. My brother was in the Air Corps in England and I got to see him on two weekends before we shipped out. Our division sailed out of Southampton, across the English Channel and landed at Le Havre, France. This port was badly damaged from D-Day (the day Allied troops first landed in Europe) and we saw several damaged ships in the harbor. Hundreds of trucks were waiting at Le Havre, assigned to our division, to help move our personnel to Germany. We traveled north through France, across southern Holland, into Belgium and across the German border south of Achen. The division moved directly to the front lines, replacing another division between November 9 and 11, 1944. It was snowing hard when this exchange was made. We went to an area Just out of a town named Eisenborn where a big battle was to be fought later on.

One of the biggest battles of the war was to start on December 17, 1944 and we were a part of it. The Germans wanted to split the Allied forces and to capture some badly needed fuel, particularly gasoline. This battle was named "Battle of the Bulge". A movie hate been made of this battle and the film is "Battle of the Bulge". It is shown quite often on TV. The Germans gathered a big part of their offensive forces and tried to penetrate the Allied lines in a pre-selected area. The 99th Division was at the northern most part of the area they started after. The mass strength of the Germans was able to make a bulge across our area of the Allied front line but the Allied forces were able to resist and drive the Germans back beyond their original starting point.

The pioneer part of the platoon name meant that we were trained to do small engineer work that could be handled without heavier equipment. Our second big truck with a winch and cable on the front of it was used to haul picks, shovels, saws, axes, chains, pulleys, mine detectors, explosives, land mines, and many other pieces of equipment that we could use to build small bridges, repair roads to make them passable, pull vehicles, trees and other obstacles out of the way. Explosives were used to get obstacles out of the way, destroy truck and guns of enemy tanks so they could not be used again and for other purposes.

The 99th Division was able to maintain their original position and turn the German invasion south so the Germans could not make the bulge larger. The 99th had done such a good job that the cress recognized their efforts by naming the Division "The Battle Babies" since they had only been in combat for a month after they got to the front lines for the first time.

The division was the first infantry division in the first Army to cross the Rhine River and the first complete division over the Rhine at Remagen. There is a movie made about the capturing of the Remagen bridge as it was very important to the advancement of the Allied forces. The movie is titled "Remagen Bridge". Your father and I walked across that bridge before it was finally damaged and also walked across the pontoon bridge the Allied engineers built to replace the original bridge.

If you are interested in following the path of the 99th Division during combat, get a map of Germany. This route will show you the land in Germany that the 99th Division covered and fought for over a period of 6 months. Start at Aachen on the northern coast of Belgium. South of this is where the Battle of the Bulge was fought. Go northeast to Dusseldorf. We were just ready to cross the Rhine River into Dusseldorf when we received orders to go to Remagen. Follow the Rhine River south from Dusseldorf to Remagen just south of Bad Godesberg. Then go directly east from Remagen to Giessen, north to Dortmund. From there the Division was transported by truck 284 miles in three days to Bamberg north of Nurnberg. On April 19 the Division started fighting its way south passing west of Nurnberg and having its last day of combat on May 2 just northeast of Munich across the Isar River near Landshut. Can you believe it snowed that last day we were in combat? V-E Day (Victory - Europe) was May 8, 1945 - what a day to remember.

Our division was then transferred to an area in the middle of Germany east of Wartburg. The 395th Division was in the Konigshofen area with our company stationed in the town of Konigshofen. I was appointed Special Service Officer for our battalion. The A&P platoon was in charge of the theater, bowling alley, and busy building softball diamonds, volleyball courts, horseshoe pits, etc.. We organized teams leagues and other activities to keep the men busy while they were waiting for orders to return to the United States and home.

The friendships that started that first week of December, 1942 at Camp Van Dorn, Miasissippiwere certainly bonded together as we lived , trained, worked and fought together as a unit. I am happy to report that no one in the A&P platoon was killed. Most of the men who started together in December 42 stayed together until the Division returned to the United States in September 1945. At that time some of the men did not have enough points to return home and were transferred to other divisions. This was the last time I saw your father so I do not know where he went or when he got home. I was transferred to four other divisions and finally returned to the United States on May 30, 1946.

Gail, I did not realize when I started this letter that it would be this long. This will probably cover many of the things your father told you about his army experiences and may add some information that you did not know about. I lived and worked very closely with your father during the entire history of the A&P platoon. He was a very dedicated and hard working man. The men of his squad respected him as their sergeant. We had a lot of good times together and I enjoyed our friendship. Again, thanks for the letter informing me about the passage of your father. The picture is also appreciated. I wish for you and your family good health and many years of happiness.

Bob McDade

Included in this wonderful trunk grouping are the following items:

- Ike jacket size 38R in excellent condition with 99th infantry division patch on the right shoulder, 4th Armored Division on right shoulder (he was transferred to 4th AD in early 1946), Gold 2nd Lieutenant bars, Sterling Silver Combat Infantryman Badge, Medal ribbons that include: Bronze Star Medal, American Campaign Medal, European–African–Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with 3 Bronze Stars, WWII Victory Medal, Presidential Unit Citation and three overseas service bars on the left sleeve indicating 18 months of overseas service. The inside of the jacket is ink marked McDade in right shoulder.

- Four pocket converted Ike jacket size 38R in excellent condition with 99th infantry division patch on the right shoulder, 4th Armored Division on right shoulder (he was transferred to 4th AD in early 1946), Silver 1st Lieutenant bars, 51st Infantry Regiment pin Back Distinctive Unit Insignias (transfered during German Occupation), incredible bullion embroidered Sterling Silver Combat Infantryman patch, Medal ribbons that include: Bronze Star Medal, American Campaign Medal, European–African–Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with 3 Bronze Stars, Presidential Unit Citation and three overseas service bars on the left sleeve indicating 18 months of overseas service. The inside of the jacket is ink marked McDade in right shoulder.

- Original WWI Officer Visor Cap, leather sweatband partially gone.

- 2 x Original WWII Army issue HBT (herringbone twill) field uniforms.

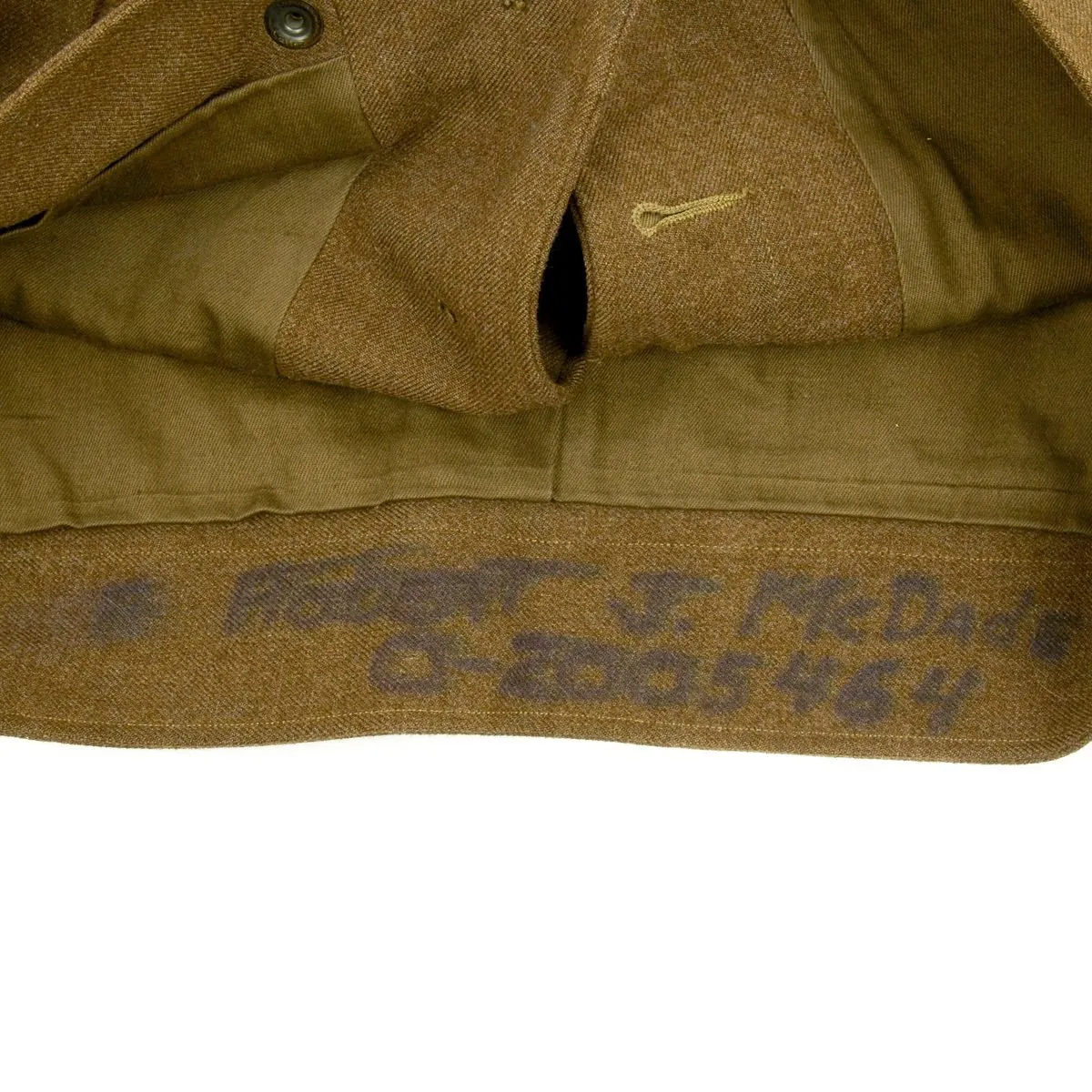

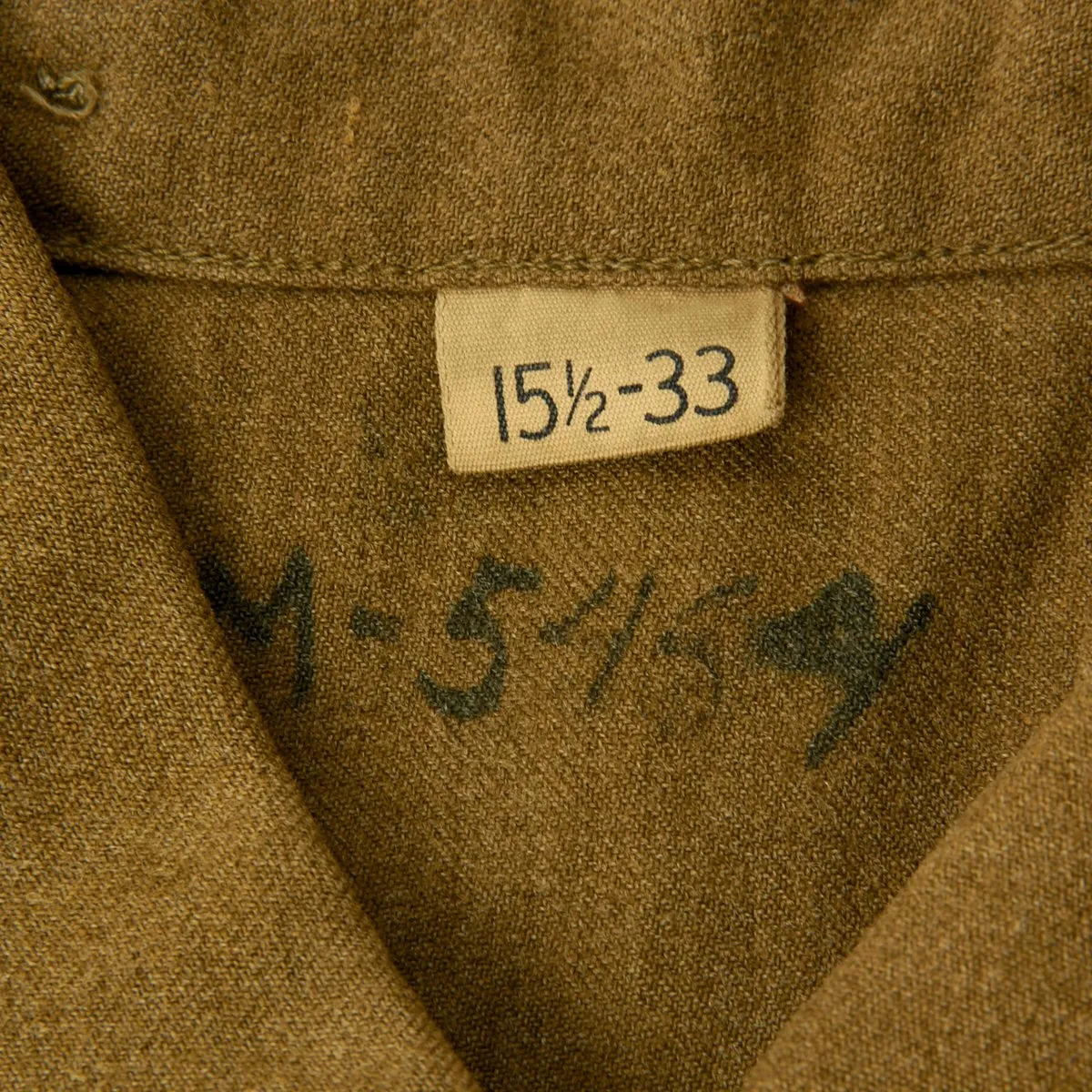

- 2 x Original WWII Army issue wool shirts.

- 2 x Original WWII Army issue duffel "stuff" bag one named in stencil to McDADE with his ASN.

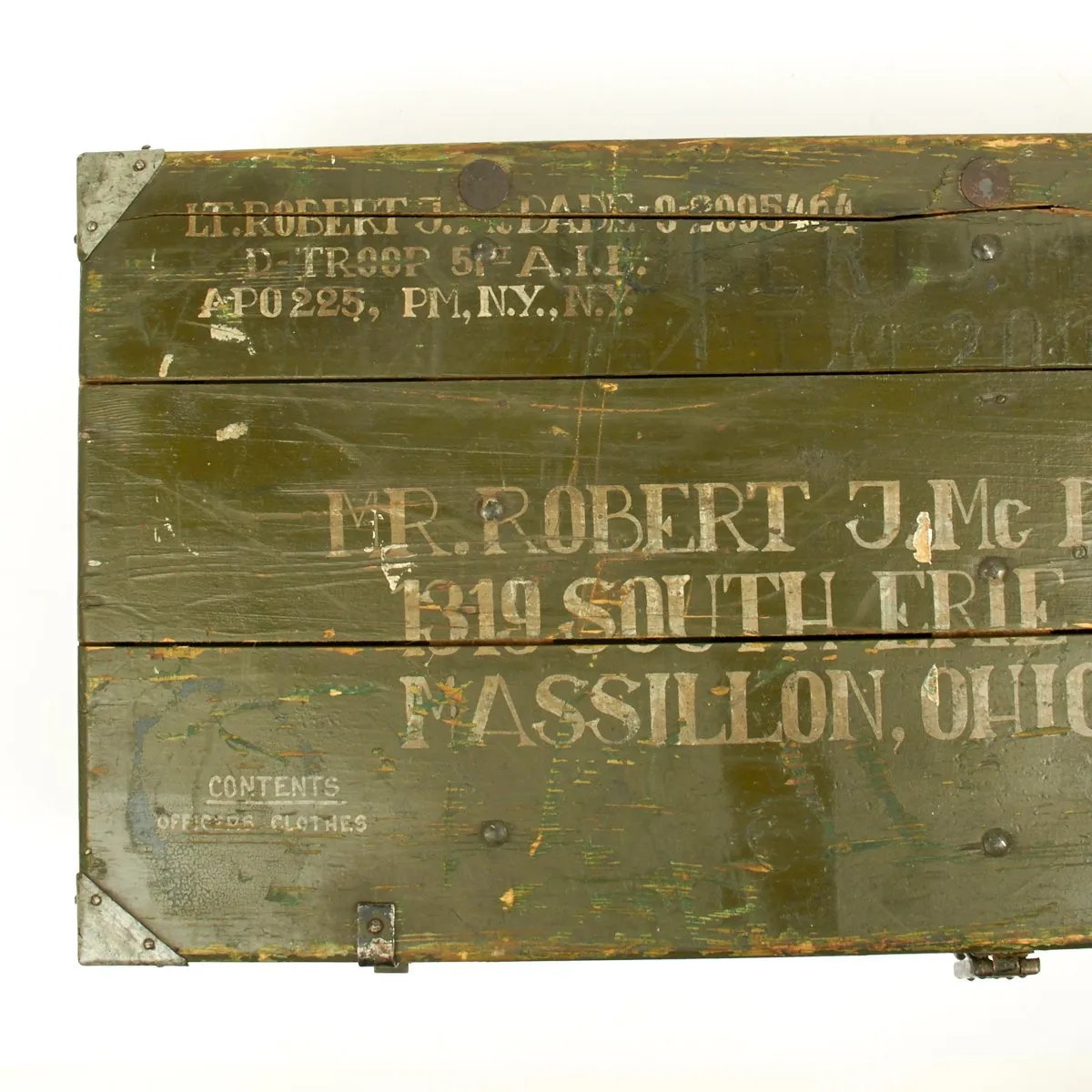

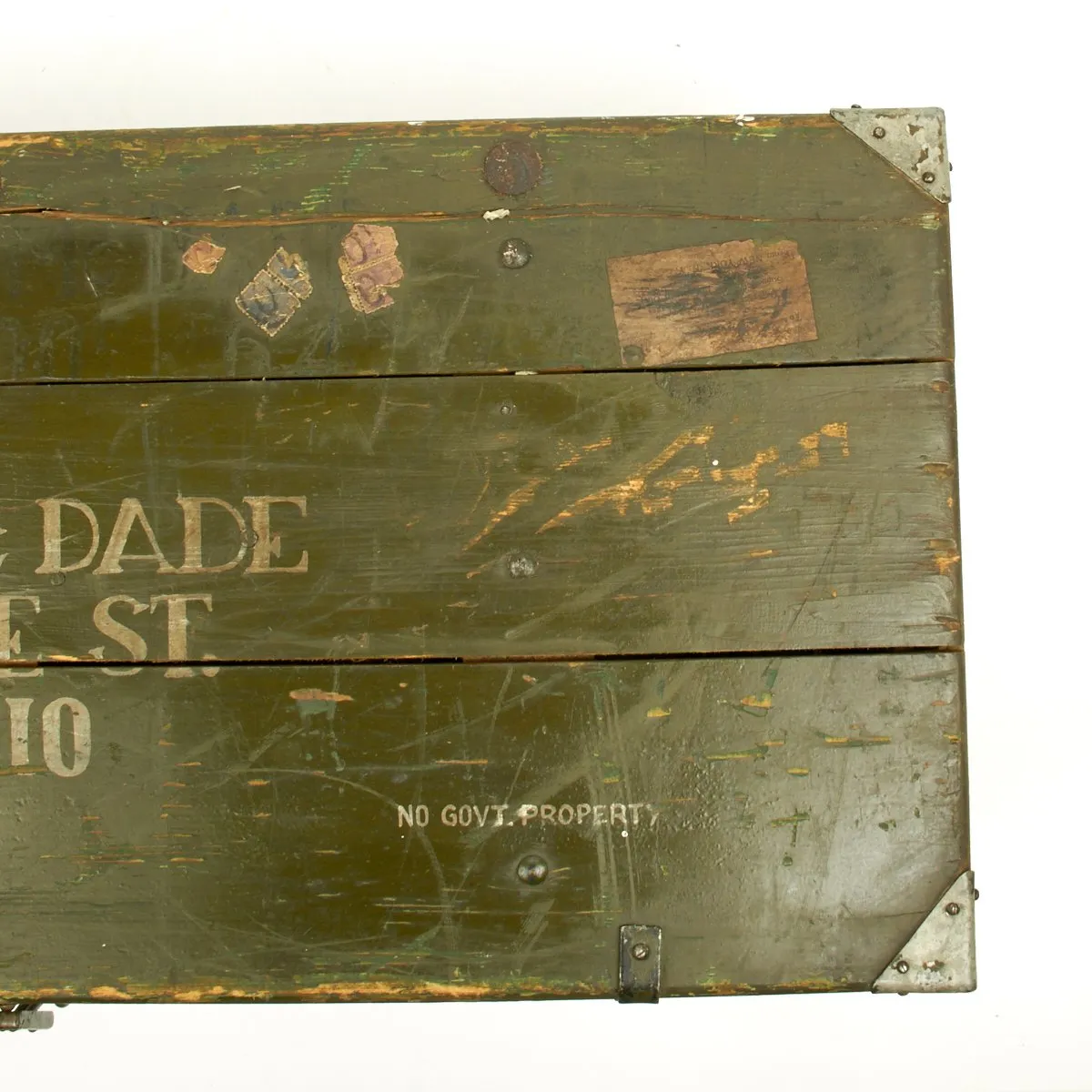

- Original WWII Wood Foot Locker Trunk stenciled to LT. ROBERT J. MCDADE with his home address in Massillon, Ohio.

- Research binder complete with copies of historical documents including obituary, two letters McDade wrote to his friend Sergeant Willard Hathaway's daughter, war time newspaper articles and more.

A wonderful grouping complete with uniform, Silver Star Medal with know citation, documents and a photograph.

History of the 395th Infantry in World War II:

The regiment arrived at Camp Van Dorn in early December. The camp was newly built, and the barracks were covered in tar paper. From Camp Van Dorn they were transferred to the more established Camp Maxey in Paris, Texas for additional training. They engaged in division-level maneuvers in July 1944. The 395th was held in the United States until more room was available for the unit to enter Europe. From Camp Maxey they took a train to Camp Myles Standish outside Boston. The 99th boarded ships bound for England on 10 October 1944 and briefly stayed at Camp Marabout, Dorchester, England.

On 5 March 1941, as the United States began to mobilize for the possibility of war, McClernand Butler became a second lieutenant in the Regular Army. Butler's great-grandfather, General John Alexander McClernand, commanded infantry during the Civil War. Butler's uncle, General Edward J. McClernand, fought in the Indian Wars and was awarded the Medal of Honor. Butler's father had been a major in the Illinois National Guard and urged his son to become a guardsman when he was 16 years old. Butler attended, but did not graduate from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He returned to Illinois and in 1933 was commissioned a second lieutenant in the National Guard. On 1 February 1944, Major Butler assumed command of the 3rd Battalion, 395th Regiment. Butler was promoted to lieutenant colonel on 21 March 1944, and remained in command of the 395th until 30 April 1945, when he collapsed from exhaustion. The war was over six days later.

The Army operated a program designed to capitalize on the large number of educated and intelligent recruits that were available. The program was called the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), and it sought to give extra training and special skills to a select group of intelligent and able young men, most of whom were taken from America's colleges. The program never fulfilled its promise, and the large number of "ASTPers" were rapidly integrated into various divisions to make up for personnel shortages in front line units during 1944. This quick infusion of personnel into the 99th Division occurred in March 1944, when more than 3000 joined the division. The sudden infusion of new men caused some friction with the old hands in the short term, but the long-term effects were generally positive. Many of the 99th Division's best soldiers were products of the ill-fated ASTP program.

Allied forces were fighting their way across France, and fresh units were badly needed in autumn 1944 to continue to press the offensive. The breakout from Saint-Lô, France was accomplished far more rapidly than Allied planners had dared hope, and American units plunged through the French countryside with undreamed of rapidity, far in advance of operational plans. American press reports from the European theater foretold the imminent fall of the Third Reich, and many men in Lt. Col. Butler's battalion thought that the war just might be over before they got there. This did not turn out to be true.

Deployment to the front

On 1 November 1944, the 99th Infantry Division, comprising the 393rd, 394th, and the 395th Infantry Regiments, was put under operational control of V Corps, First Army. On 3 November 1944, the 395th Regiment disembarked at Le Havre, France. The 395th were moved by train and truck, and finally by foot, to front line positions near the German town of Höfen a few kilometers west of the Siegfried Line and near the Belgium-German border.

No one had anticipated such a rapid Allied advance. Troops were fatigued by weeks of continuous combat, Allied supply lines were stretched extremely thin, and supplies were dangerously depleted. While the supply situation improved in October, the manpower situation was still critical. General Eisenhower and his staff chose the Ardennes region, held by the First Army, as an area that could be held by as few troops as possible. The Ardennes area was chosen because of a lack of operational objectives for the Allies, the terrain offered good defensive positioning, roads were lacking, and the Germans were known to be using the area within Germany to the east as a rest and refit area for their troops.

Col. Butler went ahead to look over the area they were assigned to defend. He found that his 600 riflemen were assigned an extremely large area about 6,000 yards (5,500 m) long without any units in reserve

That is three to four times wider than recommended by Army textbooks. I never dreamed that we would have a defensive position of this size without any backup or help from our division or regiment. When I got to Höfen, I found the area too big to cover in one afternoon. So I stayed in the village overnight.

The battalion dug in, its purpose to hold the line so that other units could attack key dams across the Roer River. In early December, the front was unusually calm and the weather was bone-chilling cold. The 99th held lines stretching from Monschau, Germany to Losheimergraben, Belgium, totaling 35 kilometres (22 mi). The 393rd, 394th, and 395th Regiments were put on line, each unit protecting approximately 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) of front, roughly equivalent to one front-line infantry man every 91 metres (299 ft). Butler held a single platoon of 40 men from Company L in reserve. In the event of an emergency, the battalion headquarters and company administrative personnel, including clerks and motor-pool staff, were to join the platoon, creating a small reserve force of about 100 men.

Around Höfen, which the 395th defended, the ground was marked with open hills. On the east lay a section of the Monschau Forest. Just south of Höfen, the lines of the 99th entered this forest, ran through a long belt of timber to the boundary between the V and VIII Corps at the Losheim Gap. The thick forest was tangled with rocky gorges, little streams, and sharp hills.

The area around Höfen and Monschau were critical because of the road network that lay behind them. During the battle to come, if the Germans succeeded in taking Höfen, their ranks would be swelled rapidly, and the 99th and 2nd Infantry Divisions would be outflanked and could be attacked from the rear. For their part, the German army was planning a seven-day campaign to seize Antwerp.

To the north of Höfen lay a paved main road that led through the Monschau Forest, at whose eastern edge it forked. A second road ran parallel to the division center and right wing, leaving the Höfen road at the small hamlet of Wahlerscheid, and continued south through two very small villages, the twin towns of Rocherath and Krinkelt. It then intersected a main east-west road at Bullingen. This was the road network the Germans needed to meet their objectives. If the Germans penetrated Höfen, the U.S. soldiers would have to withdraw several miles to the next defensible position.

Defense of Höfen

The 3rd Battalion, 395th Infantry, led by Lt. Col. McClernand Butler, occupied the area around Höfen, Germany, on the border with Belgium during early December. The terrain was open and rolling, and over six weeks the 3rd Battalion prepared dug-in positions that possessed good fields of fire. The 38th Cavalry Squadron (led by Lt. Col. Robert E. O'Brien) was deployed to the north along the railroad track between Mutzenich and Konzen station. The 1st Battalion was positioned on the right. The infantry at Höfen lay in a foxhole line along a 910 metres (2,990 ft) front on the eastern side of the village, backed up by dug-out support positions. These would later prove instrumental in defending themselves from the attacking Germans and in protecting themselves when their own artillery fired on or just in front of their own positions, which happened at least six times over the next few weeks. They inflicted disproportionate casualties on the Germans, and were one of the only units that did not give ground during the Battle of the Bulge.

Because of the success of the 395th and the 99th, the Americans maintained effective freedom to maneuver across the north flank of the German's line of advance and continually limited the success of the German offensive.[

Disproportionate German casualties

The 395th hit the Germans with such terrific small arms and machine gun fire that they couldn't even remove their dead and wounded in their rapid retreat.[16] The accurate fire from the 12 3 inch guns of A Company, 612th Tank Destroyer Battalion, was instrumental in keeping German tanks from advancing. During the first day of the Battle of the Bulge, the 3rd Battalion took 19 prisoners and killed an estimated 200 Germans. Accurate estimates of German wounded were not possible, but about 20 percent of the 326th Volksgrenadier Division were lost. The 395th's casualties were extremely light: four dead, seven wounded, and four men missing.

On another day, the 3rd Battalion took 50 Germans prisoner and killed or wounded more than 800 Germans, losing only five dead and seven wounded themselves. On more than one occasion, BAR gunners would allow Germans to get within feet of their positions before opening fire, with the objective of increasing the odds of killing the attacking Germans. "In two cases, the enemy fell in the BAR gunners' foxholes." On at least six occasions they called in artillery strikes on or directly in front of their own positions.

As the battle ensued, small units, company and less in size, often acting independently, conducted fierce local counterattacks and mounted stubborn defenses, frustrating the German's plans for a rapid advance, and badly upsetting their timetable. By 17 December, German military planners knew that their objectives along the Elsenborn Ridge would not be taken as soon as planned.

The 99th as a whole, outnumbered five to one, inflicted casualties in the ratio of eighteen to one. The division lost about 20% of its effective strength, including 465 killed and 2,524 evacuated due to wounds, injuries, fatigue, or trench foot. German losses were much higher. In the northern sector opposite the 99th, this included more than 4,000 deaths and the destruction of sixty tanks and big guns.

On 28 January 1945, after six weeks of the most intense and relentless combat of the war in the biggest battle of World War II, involving approximately 1.3 million men, the Allies declared the Ardennes Offensive, or Battle of the Bulge, officially over. The 3rd Battalion, 395th Regiment had acquitted itself with valor, having held its lines despite the harsh winter weather, the enemy's numerical superiority and greater numbers of armored units.

Awards

The 3rd Battalion received a Presidential Unit Citation for its actions around Höfen from 16 to 19 December. It was credited with destroying "seventy-five percent of three German infantry regiments." The citation read:

During the German offensive in the Ardennes, the Third Battalion, 395th Infantry, was assigned the mission of holding the Monschau-Eupen-Liege Road. For four successive days the battalion held this sector against combined German tank and infantry attacks, launched with fanatical determination and supported by heavy artillery. No reserves were available . . . and the situation was desperate. On at least six different occasions the battalion was forced to place artillery contingents dangerously close to its own positions in order to repulse penetrations and restore its lines . . .

The enemy artillery was so intense that communications were generally out. The men carried out missions without orders when their positions were penetrated or infiltrated. They killed Germans coming at them from the front, flanks and rear. Outnumbered five to one, they inflicted casualties in the ratio of 18 to one. With ammunition supplies dwindling rapidly, the men obtained German weapons and utilized ammunition obtained from casualties to drive off the persistent foe. Despite fatigue, constant enemy shelling, and ever-increasing enemy pressure, the Third Battalion guarded a 6,000 yards (5,500 m)-long front and destroyed 75 percent of three German infantry regiments.

General Order Number 16, 6 March 1945

The 395th, entrenched along the "International Road" and Elsenborn Ridge, forced the Germans to commit and sacrifice many of their infantrymen and expose their armored formations to withering artillery fire.[19] The regiment's successful defense prevented the Germans, who had counted on surprise, numbers, and minimum hard fighting as their keys to success, from accessing the best routes into the Belgium interior, and seriously delayed their scheduled advance by more than 48 hours, allowing the Americans to move large numbers of units and bring up reserves.

Enemy respect in combat

German prisoners captured during the Battle of the Bulge volunteered praise of the 99th's effective defense of Höfen. A captured Lt. Bemener, formerly commander of the 5th Company of the 753rd Volksgrenadier Regiment, asked his American interrogator about the unit that had defended Höfen. Told it was the 3rd Battalion, 395th Infantry, he said, "It must have been one of your best formations." Asked why he thought so, he said, "Two reasons: one cold-bloodedness; two efficiency." Another German officer who was captured said, "I have fought two years on the Russian front, but never have I engaged in such a fierce and bloody battle."

Two Distinguished Service Crosses and several Silver Stars were awarded to members of the battalion for valorous actions against the enemy during this battle. Sgt. T. E. Piersall and Pfc. Richard Mills were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Additional offensive operations

After a short period off the line, the battalion conducted offensive operations in Germany, including the seizure of several German towns from 1 to 5 March.[14] The first town they were tasked with capturing was Bergheim, "the door to the Rhine." Butler's regiment crossed the Erft Canal near the Rhine and enlarged the bridgehead, taking that town with a night attack without losing a single man. Butler said, "The biggest difficulty in carrying out a night attack is control, and having men who can coordinate well as a team in the dark. I decided to stage the night attack at Bergheim because my troops would be going across an open area about 500 yards (460 m) long and 400 yards (370 m) wide. There was no cover. It was like a golf course, so I used the night for concealment."

The 395th Regiment's success earned it many difficult assignments. A U.S. Army World War II division was configured as a Triangular division, with three regimental maneuver elements. Up to that point, the Army had married a battalion of tanks to a battalion of infantry in support of the tanks. But the infantry often bore worse casualties than the tanks did and had to be replaced and reinforced more quickly. This required the corps commander to draw on an infantry battalion from another division, and because of the reputation the 395th had earned at Höfen, it was transferred often to various divisions, including the 9th Infantry Division, the 3rd Armored Division, and the 7th Armored Division. "Blue" was the code word for the 3rd battalion under Army infantry's triangular organization.

The town of Kuckhof cost the battalion dearly, with more than fifty casualties inflicted on one company alone (I Company). The remainder of the battalion reached the Rhine River on that same day and crossed the Remagen Bridge which four days after being captured was still being shelled by German artillery. They then crossed the Wied River, where they joined up with the 7th Infantry Division. They were tasked with moving 10 miles (16 km) behind the German lines and cutting the Autobahn to prevent the withdrawal of the Germans.

They continued to fight even as the American press trumpeted the rapid crumbling of German resistance. The regiment helped to capture the Ruhr Pocket, where thousands of German troops and hundreds of German vehicles were captured. The unit crossed the Altmuhl River on 25 April, the Danube River on 27 April, and the Isar River on 30 April. There Major Butler collapsed due to exhaustion on 30 April, and Lt. Col. J. A. Gallagher assumed command for the last few days of the war. When hostilities ceased on 7 May 1945, the regiment had during six months of fighting experienced 300 percent turnover due to casualties. The regiment assumed occupation duties in Hammelburg and Bad Bruckenau until it was shipped home in the summer of 1945. Lt. Col. Butler retired from the Army on 14 January 1946 and worked for the phone company for the rest of his career.